Pinky on Caravaggio

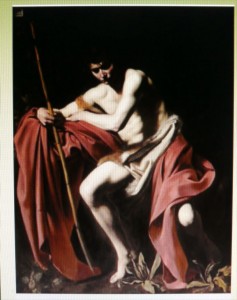

Many years ago when I was in graduate school we played a little game in which there was a fire at the Nelson Gallery and we could only save one painting. My mission would be very clear; I would single handedly haul the huge Caravaggio painting of St. John the Baptist to safety. I knew a few delicious salacious facts about the artist and I knew a wee bit more about baroque painting. A huge greatest hits exhibition of his work has just closed in Rome after having drawn thousands of visitors; that such a show would take place in Rome is not surprising in that a majority of Caravaggio’s accepted 60 works are in situ there. BUT one of the hits of the exhibition is the St. John the Baptist loaned by the Nelson Gallery in Kansas City. And so, to capitalize on this interesting fact, let’s just talk a little about this work and the artist who painted it.

Caravaggio arrived in Rome as Michelangelo Merisi from the town of Caravaggio in 1592 as a youthful aspiring painter. It took only a few years for his unconventional aesthetic vision and colorful often violent lifestyle to transfix Roman society. Today he is accepted as the ultimate Baroque painter, so much so that he is eclipsing Michelangelo Buonarotti in academia publishing. (This may well be because nothing is left to say about the Sistine Ceiling and the David and the Pieta.) As Michael Kimmelman reports, “By at least one amusing new metric; Michelangelo’s official 500 year run at the top of the Italian art charts has ended. Caravaggio, who somehow found time to paint when he was not brawling, scandalizing pooh-bahs, chasing women (and men), murdering a tennis opponent with a dagger to the groin, fleeing police assassins or getting his face mutilated by one of his many enemies, has bumped him from his perch.” His St. John the Baptist is a life size smoldering youth with dirty toenails placed in such a position that he demands the viewer to pay attention to him. He shares our space and we his, face to face, something that does not happen with Michelangelo’s enormous sculptures. The immediacy somehow dovetails with the tabloid tawdriness of his life and the whole modern celebrity drama. Painted at the height of his career in Rome this 1604-05 work depicts the brooding intensity of St. John dramatized by the strange lighting that is known as chiaroscurro which rakes the body diagonally pointing up the head and body while obscuring all but the knee of one leg. Caravaggio may have borrowed the pose from one of Michelangelo’s seated prophets in the Sistine ceiling but this St. John is not an over muscled titan; he is pensive and representative of the Counter Reformation, which was an attempt to bring its viewers back to the true faith of the Roman Catholic church with realism, simplicity, and piety in art rather than with the Inquisition which had failed to do so. Caravaggio connected with ordinary people, the ones who themselves arrived barefoot and filthy as pilgrims in Rome, but he also appealed to a string of rich and powerful patrons. Almost all of his models came from the streets he walked each day, and from his circle of friends and acquaintances: swordsmen, painters, commoners and courtesans. Yet his patrons were primarily the wealthy cardinals of the church. As a matter of fact, some of his works are in the collection of Cardinal Borghese were thought to be gifts from Caravaggio for getting him out of various legal entanglements, and perhaps the murder charge.

It has been said that he was just another young aspiring painter but his unconventional aesthetic vision and colorful, often violent lifestyle transfixed Roman society. In 1601 he received a major commission for Santa Maria del Populo for a Conversion of St. Paul and a Crucifixion of Saint Peter. In the conversion a bright shaft of light carries symbolic meaning, indicating the bestowal of Christian faith upon Saul who thereafter became Paul. It shows Paul struck from his horse in the conversion and depicts the rear end of the horse with the stricken saint; detractors referred to the painting as “an accident in a stable.” Similarly the brutality of Peter being crucified upside down in order to lengthen the agony of hiss suffering created anguish in the viewers, but this was a way to dramatize the story. His first attempts were rejected but his second take on the scenes provided a striking contrast to the altarpiece Assumption of the Virgin by Annibale Caracci, another star of the time. While there were some who denied his talent and denigrated his lifestyle, we must think in terms of his creativity. Caravaggio spent the last four years of his life on the run, a death sentence hanging over his head as a result of the murder over a tennis match. He wandered btween Naples, Malta and Sicily and died in the summer of 1610 in mysterious circumstances, as he was returning to Rome after receiving a papal pardon for the murder. His impact on the art of his century was still considerable, but he had discouraged potential students preferring to paint not teach or manage. His works had a theatricality that did not wear well with later critics and his work lapsed into relative obscurity until it was rediscovered in the last years of the 19th century. From that time it has been a gradual revival of appreciation of Caravaggio’s talent.

Today we face the dilemma of fame that ties the artist to his work. There is a tendancy to retell the stories of his jail sentences, his drinking and carousing, his fleeing police assassins, and brawling in the streets as the plight of van Gogh, the arrogance of Gauguin, or the drunken Jackson Pollack seem to bring to these painters a form of fascination and respect which has little to do with the art that is created. Yes it is true that none of these painters lived in ivory towers and that their tumultuous lives must reflect in some way their feelings in their works of art. But to glory only in the bad boy aspects of any painter is to miss the point of their works. Caravaggio may have been noted for his swordmanship by his contemporaries but the real contributions of his art was the departure from the elegant elongated figures of the Mannerists and the use of both realistic types and strong chiaroscuro. He brought new life and immediacy to painting and a naturalism which flourished in Italy and abroad. And yes, I would still rip John the Baptist off the museum wall and save it from the fire.

Leave a Reply